the call stack, web apis, and the event loophow javascript fakes its way through async

minute read

JavaScript is a single-threaded language. You might be thinking, what the heck is a single thread? That’s a good place to start, and an important aspect of what’s really going on under the hood.

Single-threaded means that JavaScript can only do one thing at a time. A JavaScript program runs from top to bottom, start to finish, executing each line of code in the order that it was written, much like reading a book. But what if, like a book, we have a subplot that’s going to take some time to cook up. Should we stop reading the story, and focus completely on building up the subplot? Of course not, that would pull us too far away from the main storyline, and drag down the rest of the novel. The same is true for JavaScript. To solve this problem, JavaScript has some special implementations that can be used to defer some code to be run at a later time.

Enter asynchronous JavaScript, commonly referred to as async.

If code is considered synchronous, then the code runs just as it reads: top-to-bottom. Everything happens in the same order, one after the other. Asynchronous, on the other hand, means that the code is able to run concurrently.

You might be thinking, if JavaScript is single-threaded, and can do only one thing at a time, then how do we bend the language to run multiple things at once? That’s where things get a little strange. Technically, things are not running at the same time, though the output of your application might appear like they are.

Well, then? How does it work?

Before we can dig into that, we need a solid understanding of what the call stack, commonly referred to as the stack, is, and what it does for us.

We expect that when the function is called with sayHello('Kobe');, we’ll see Hi Kobe print out to the console. Pretty straightforward; JavaScript is only doing one thing. Let’s add another simple function to this program.

Now, JavaScript needs to do two things: run sayHello('Kobe'), then printUserAge(30). When this code runs, it appears to happen instantaneously. We’ll see both results (Hi Kobe and The user is 30 years old) print to the console right away, one after the other. But something more is happening behind the scenes.

First, both functions are initialized. JavaScript reads over them, and commits them to memory to be used later, when they’re actually called at the bottom of the script. It’s when JavaScript reaches those function calls that things get a bit more interesting. JavaScript reads sayHello('Kobe') and adds its execution to the stack. The stack is where JavaScript does all the heavy lifting, actually running the function, instead of just keeping its instructions in memory.

With functional programming, you can think of the stack like a pile, or stack of books or movies (we’ll get further into that later). However with simple, independent functions like these, it’s more akin to sliding a disc into your BluRay player. You can only play one disc at a time, and need to take the disc out before you can add another.

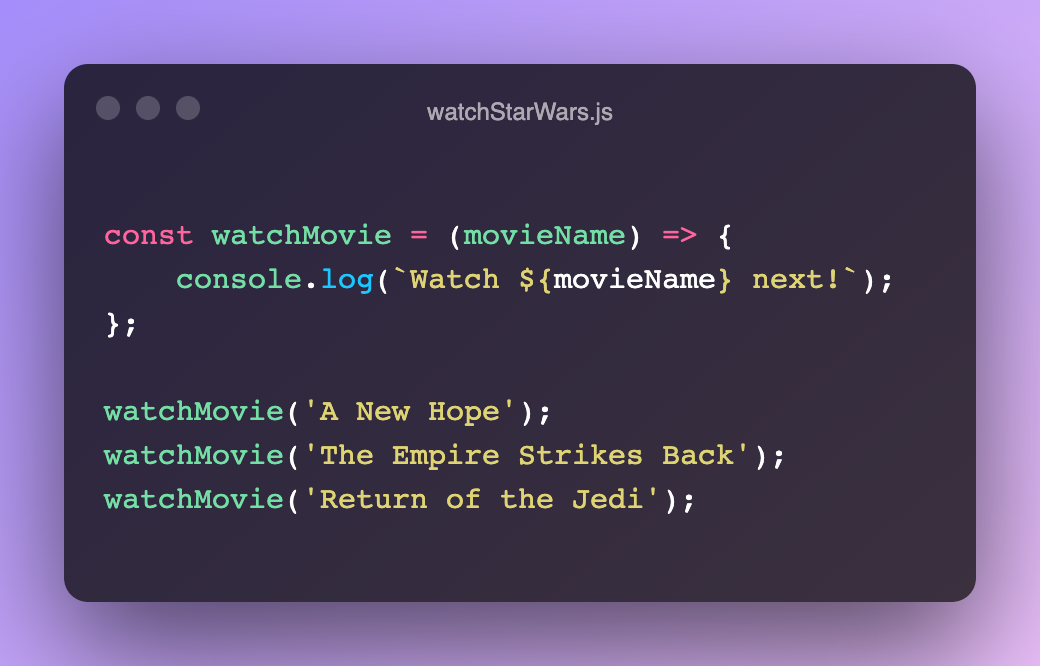

Let’s take the original Star Wars trilogy (A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back, and Return of the Jedi) as examples. And you can think of our program, or script, like instructions for watching those movies. We should start with A New Hope, then watch The Empire Strikes Back, then finally Return of the Jedi. If these instructions were written in JavaScript (rather crudely), they might look something like this:

The same watchMovie() function is called three times, each time with a different argument to let us know which movie we should watch next. When the function is called, it is added to the stack, executed, then removed from the stack. Only when the function is removed from the stack will the execution continue from watchMovie('A New Hope') on to watchMovie('The Empire Strikes Back'). Throughout the above code, the call stack’s size does not exceed one.

The output we’d see in the console would look like this:

Watch A New Hope next!

Watch The Empire Strikes Back next!

Watch Return of the Jedi next!

So far so good. JavaScript only begins executing the second function call, watchMovie('The Empire Strike Back) once the code preceding it, watchMovie('A New Hope'), has completed.

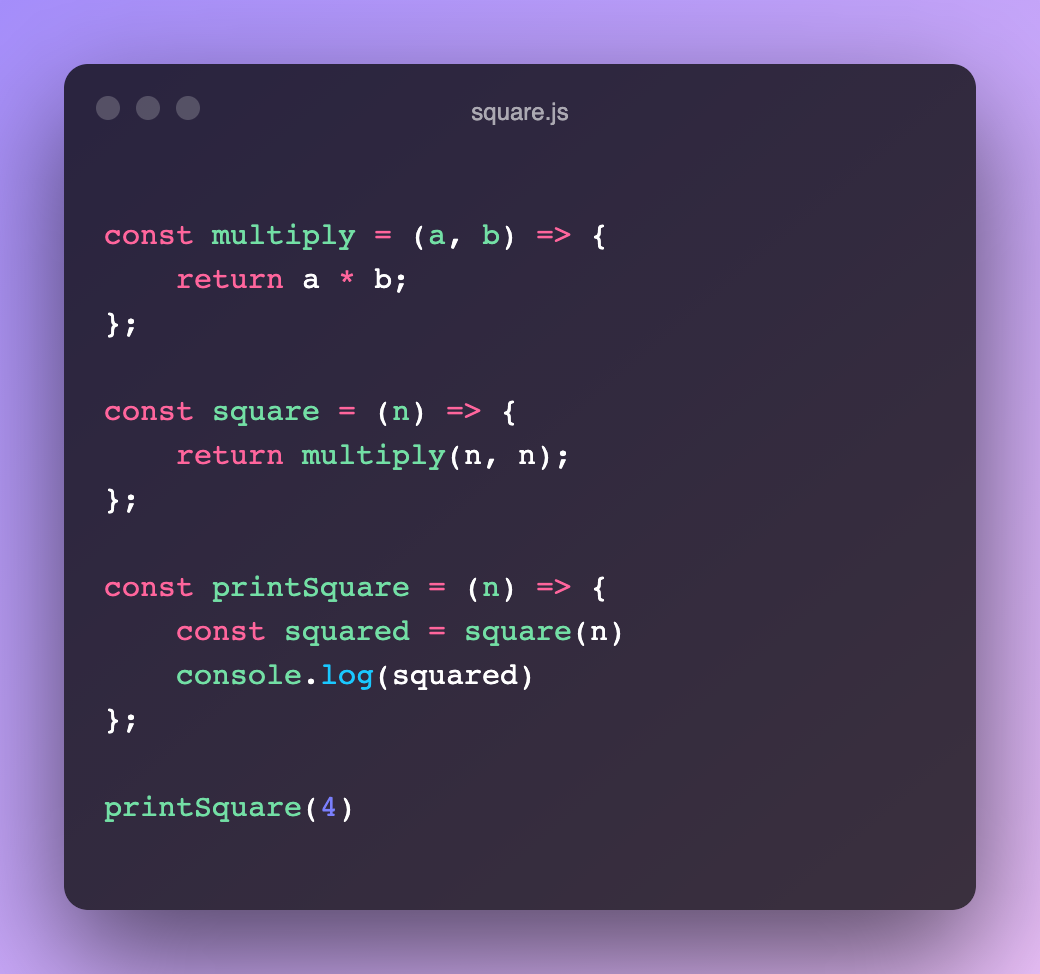

Let’s take a look at a few more functions. This time, we’ll cause the stack to pile up a bit.

- printSquare(4) is called, and it’s added to the call stack.

- WithinprintSquare(4), the square(n) function is called. It’s added onto the top of the stack too.

- Within the square block, multiply(n, n) is called, and added onto the top of the stack.

At the moment, the call stack would look a bit like this:

Before we can actually run square(n) or printSquare(4), we need to work our way through the stack, from top to bottom. It first returns multiply(n, n), then square(n), then printSquare(4), where 16 is finally printed to the console.

Within reason, there’s nothing wrong with piling things up on the stack. It can hold just about anything you can throw at it. That said, it is possible to exceed the stack’s limit; what’s often called a stack overflow, or blowing the stack. When it happens, you’ll see an error message along the lines of Maximum call stack size exceeded—something that you probably came across once or twice while getting familiar with loops.

Okay, so you’re feeling a bit more comfortable with the call stack. But how does async fit into all this? If we can only do one thing at a time, doesn’t that mean that JavaScript is always synchronous?

Web APIs, the callback queue, and event loop

To achieve this simulated functionality of multithreading, in conjunction to the call stack, JavaScript uses some built in Web APIs, a callback queue, and an event loop. Together, they ensure the stack doesn’t get bogged down with a more intensive task, which are aptly referred to as blocking tasks or actions. If it does, no matter how simple or complex the executions following the blocking task are, JavaScript waits for the blocking task to finish before continuing with the program.

The DOM, XMLHttpRequest, and setTimeout are examples of Web APIs

But wait, before we get too far in, why does this even matter? When would we need something to be asynchronous anyways?

Most JavaScript executes immediately; you’ll see the result in fractions of a second. But some code, especially code that communicates with a server (think API GET requests), can often take several seconds, possibly minutes, or might even fail entirely. During that time, while JavaScript is waiting for the response so it can continue on with whatever else you’ve instructed it to do, no other JavaScript on your page will be able to run. It’s stuck. JavaScript runs on the browser’s main thread; when that thread gets stuck, the entire page gets stuck too. The main thread is blocked, your application freezes, and, until the blocking action is completed, will be non-responsive to your users.

When we instruct JavaScript to run something asynchronously, instead of adding it to the call stack, JavaScript moves it over to a separate stack-like data structure, where it’s first handled by the Web APIs. From the Web APIs, the task is then transferred to the callback queue. The aptly named callback queue queues up each task from the Web APIs in the order they were received. They do not run yet. Actions in the callback queue are simply waiting in line, before they can hop onto the call stack and run.

So when does the code actually run? When does it get to jump onto the call stack and execute?

Not until the stack is clear.

All of your program’s synchronous code will hop on and off the call stack, while passing any async operations to the Web APIs, and callback queue. Finally, when the call stack is clear, and all synchronous code has been executed, the event loop begins passing the actions from the callback queue onto the stack, allowing each action to execute completely before passing the next onto the stack. When the current async operation clears from the stack, the event loop adds the next action from the callback queue onto the stack. This pattern continues to repeat until the stack and callback queue are both empty.

As we’ve learned, JavaScript really doesn’t run asynchronously. Instead, it creates the illusion of concurrency by running what it can immediately, and running its more intensive parts afterwards. Usually, this all happens quickly enough for the output we see to appear seamless, to the point it’s referred to as asynchronous.

The concept of a stack isn’t unique to JavaScript. Getting familiar with its inner workings in JavaScript will serve your understanding of other languages well too.